While beauty is in the eye of the beholder, it’s unlikely that an oyster is ever going to win the Bonnie Baby competition. Virtually colourless and often found plastered in mud, it struggles to hold a candle to many more ‘attractive’ molluscs. But as they say, looks aren’t everything and there is more to the humble oyster than most of us might imagine.

Surprisingly, Ostrea edulis has much in common with the more charismatic Eurasian beaver. Like the beaver, the native oyster is a keystone species: an incredible ecosystem engineer, with the ability to help us restore abundance and diversity to Scotland’s seas. While the work of the beaver can help mitigate flooding and filter harmful chemicals through its extensive dam building, the oyster similarly filters huge amounts of water – more than 200 litres every day. It removes pollutants, chemicals, effluent and particulate matter, and like beavers, oysters help sequester carbon, as well as creating complexity in their environment through their intricate three-dimensional reefs, which provide sanctuary for a vast array of marine life.

Once found all around our coastline, oysters have been over-used and abused, their fragile habitat dredged and trawled to the point where they are now endangered. While giant pandas and tigers grab the conservation headlines, the plight of this non-descript but essential mollusc goes largely un-noticed.

Oysters filter huge amounts of water – more than 200 litres every day – removing pollutants, chemicals and particulate matter.

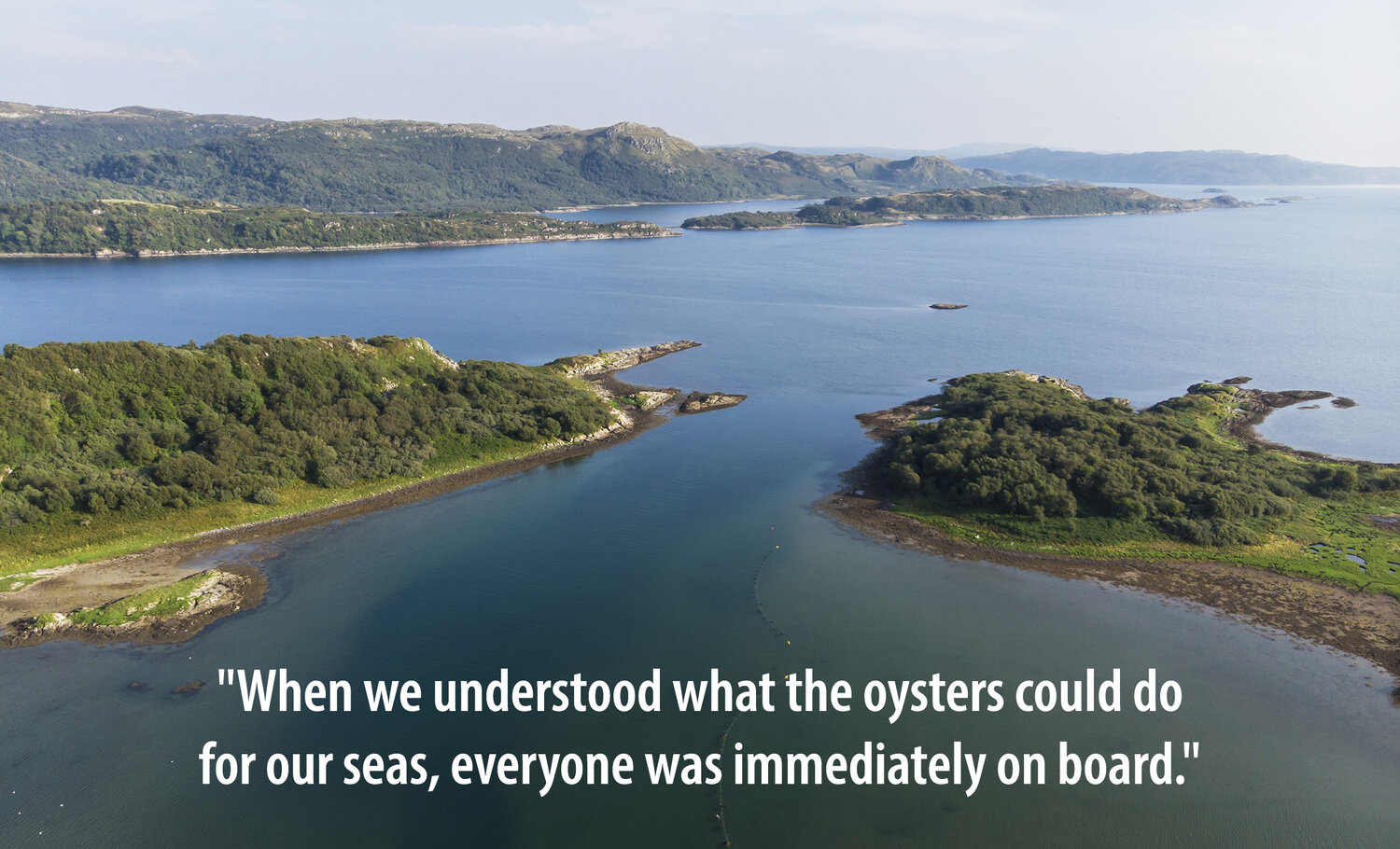

So, what can be done to reverse the tragic demise of this marine treasure? People power is the short answer. Nestling south of the vibrant port of Oban, a small rural community on the Craignish peninsula is well aware of the oyster’s potential. In 2016, concerned about the effects of over-fishing, dredging and plastic pollution in the glorious but susceptible Loch Craignish, a group of volunteers formed the Craignish Restoration of Marine and Coastal Habitats, or CROMACH for short. The group aims to promote and protect the surrounding marine environment and top of their ‘to do’ list is the return of native oysters to the sea loch.

The area has been designated as a ‘Hope Spot’, the first of its kind in Scotland. Established by Mission Blue, an organisation led by the legendary oceanographer Dr Sylvia Earle, Hope Spots are special places identified as critical to the health of the planet’s oceans. The Gulf of California is a Hope Spot; so too the Sargasso Sea and the Maldive Atolls. The Argyll Coast & Islands sits alongside the great and the good of the world’s marine ecosystems.

Antonia Baird, the enthusiastic Chair of CROMACH, grew up here. “My family have been here for generations and I know how glorious it is, but we also know we need to look after what we have. We heard about oysters and we knew there was still a tiny population in the loch, but when we understood what they could do for our seas, everyone was immediately on board.”

In 2019, following a series of meetings, presentations and school visits, CROMACH secured a small SeaChangers grant to cover a pilot study into the feasibility of returning these native bivalves to the loch.

“There’s a baffling amount of red tape and bureaucracy, but eventually we secured a licence and worked closely with NatureScot to ensure that biosecurity protocols were followed.” Antonia smiles before continuing. “We then introduced a thousand tiny baby oysters into specialised cages. They did well, and the project for a large-scale reintroduction was born.”

CROMACH is an eclectic mix of people of all ages, united by a strong connection to this place. “There are many important players who have made this possible – too many to mention – but it needed a driving force and Danny Renton, or Mr Oyster as we now call him, is that force. We could not have come this far without him.”

A grant from the National Lottery Heritage Fund meant that a five-year project could kick off to grow 1 million juvenile oysters in specialist floating cages. Once mature they will be translocated to trial seabed sites around Loch Craignish.

“It’s incredibly exciting,” Antonia explains. “All the bits interlock nicely both ecologically but also from a community perspective. Our members range from academics to hands-on volunteers, to primary school children, yachtsmen and visitors, some of whom have been coming here for years. Everyone feels a part of this.”

Ardfern seems idyllic on a hot August day with not a midge in sight. It’s a village that still has a school, and a village shop – increasingly rare in a world of change. Before meeting Mr Oyster, I chat with another driving force, the charismatic wildlife photographer and guide Philip Price, who has been in the thick of this since its conception. He, his artist wife and their triplets lead a mainly green existence – growing their own fruit and vegetables, and getting about on an electric bike, with a capacious trailer that Philip uses to transport clients to his wildlife hides. “We needed a united community voice to help us make vital decisions on how we use our seas. We want to have the power to say ‘stop’ to unsustainable fishing and development, because we won’t get a second chance” says Philip, a passionate advocate for all aspects of rewilding.

Danny is as equally charming and charismatic and although widely recognised as the instigator of the oyster reintroduction, he is quick to point out the key role of others. “John Hamilton of Lochnell Oysters has advised us and helped us all the way. He designed and developed the ‘oyster hoisters’ to hang under the marina pontoons at the Ardfern Yacht Centre. Each hoister houses thirty mature oysters all of which will release spat. Yacht owners can sponsor a hoister and become active stakeholders. In this way, they can put something back into the marine environment.”

Oysters fascinate children and Danny’s own charity Seawilding, has partnered with Heart of Argyll Wildlife, a local environmental group run by Pete Creech and Oly Hemmings, who will be working with primary-aged children drawn from five local schools. They will record weather, sea condition and temperature, and gather data on the oyster’s growth rates. They will examine predation and mortality levels, while also studying the other creatures that share the oyster’s space. The presence of non-native marine species, perhaps introduced on boat hulls, will also be logged. “We’ve rented a room in the Craignish Hall opposite the marina so on bad weather days after looking at the oysters and seeing their progress, we can run our workshops for the children there. This is great for engaging the children, but it’s also an important citizen science project,” Pete Creech tells me.

Students from the Scottish Association of Marine Sciences (SAMS) as well as from Stirling University’s School of Aquaculture will also monitor the project’s progress once the young oysters have become established on the seabed. Alongside several other restoration projects across the UK, the data gathered will feed into the wider effort to restore oyster reefs.

Danny and I head to the shoreline. Loch Craignish is as smooth as silk, clear as gin and fringed by swathes of purple loosestrife, yellow hawkweed and meadowsweet. Bees and grasshoppers thrum and tick. We drag a small boat down across a patch of yellow sand, and Danny rows us out to the newly established oysters drifting in cages off a small island, Eilean Buidhe.

They have been out here now for three weeks. After two years in the planning, 60,000 juvenile oysters, the size of a thumbnail, arrived from a Morecombe Bay hatchery. It was a great moment. Finally, Scotland’s first community-led marine habitat restoration project was underway.

The oars click and splash as we chat and quickly reach the floating baskets. Danny pulls one up – seaweed festoons the container. The oarsman carefully takes a handful of little oysters from their refuge.

“Look at this, they’ve grown already – see that pelmet around the shell, that’s new growth. In the next five years, we hope to put in a million young oysters. When they are around the size of a 50p piece, we will return them to the seabed having first located safe sites that have been surveyed by divers.”

But his brown weather-beaten face creases with concern.

“Ultimately, if this is to succeed, we need a Marine Protected Area for Loch Craignish for community-led research and habitat restoration. We need to keep the scallop dredgers out as they can destroy our work in minutes.”

Danny is ambitious and highly driven. He would like to see the eventual establishment of a sustainable local fishery. “It would provide jobs, and we could grow other things – seaweed, and mussels – a regenerative polyculture. If we can take people with us, the model we are creating is infinitely replicable elsewhere. It’s a project that could be rolled out all around Scotland. People are increasingly aware of what is happening on land, but not at sea. Many local fisheries are dead or dying but rather than simply lament that, we want to do something positive.” He smiles as he returns the baby oysters to their floating home, and then rows us gently back to the beach.

I think of a favourite quote by Margaret Mead: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has.” Beautiful Loch Craignish is rightly a Hope Spot. And hope is what we need.